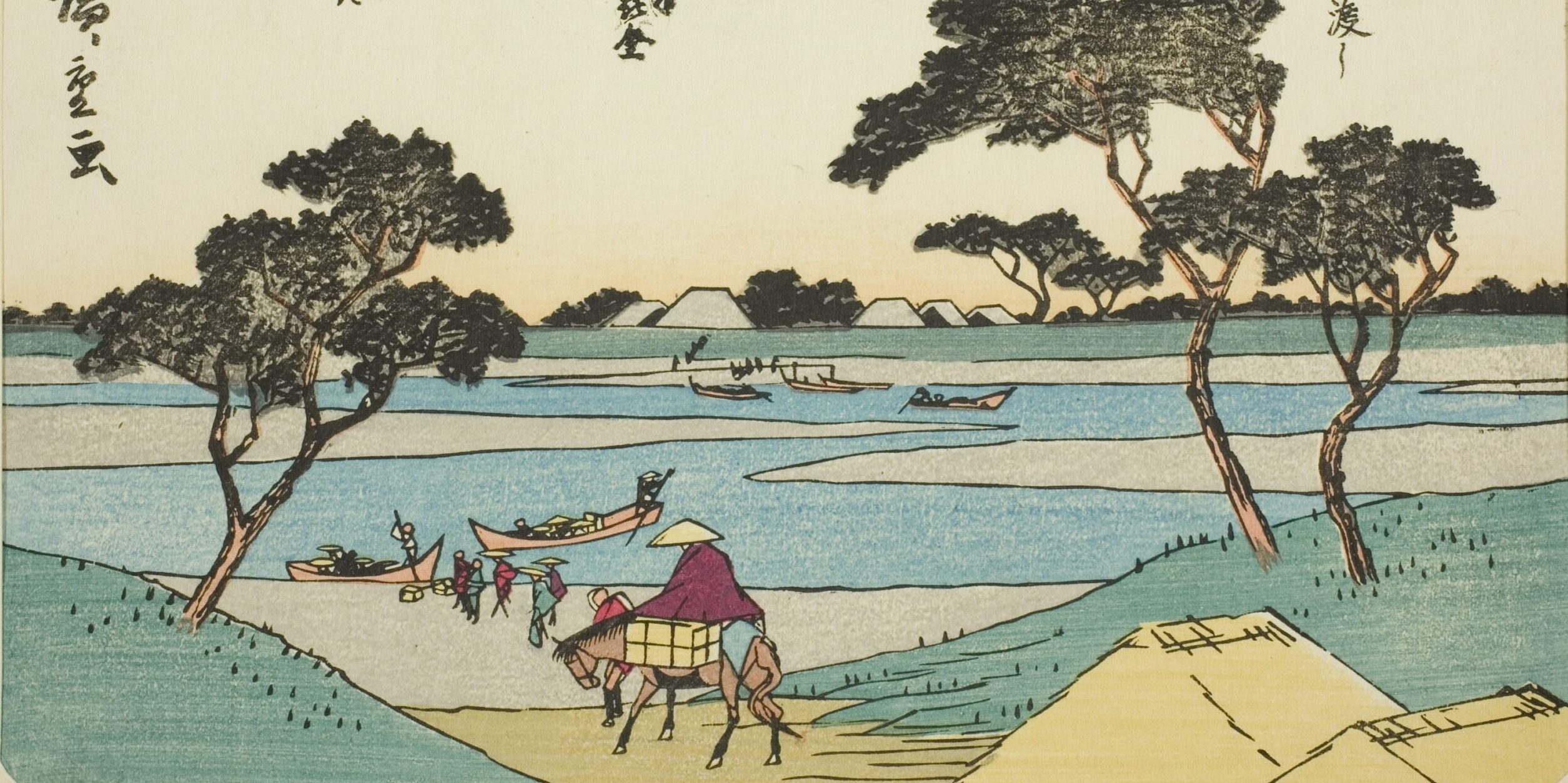

Mitsuke: Ferries Crossing the Tenryu River by Utagawa Hiroshige, c. 1837 – 42

The quest to find the meaning of our life is a universal human experience. We often feel an intrinsic drive to understand our purpose and place in the world. Indeed, psychologist Viktor Frankl – a survivor of the Holocaust – observed that even in the harshest conditions, those who found meaning in their lives were more resilient and hopeful.

Humans, driven by an insatiable curiosity, inevitably contemplate the profound meaning of life, as if the world itself holds the key to understanding its intricate connections. Unlike other animals, we think about the future and seek purpose beyond immediate survival. Frankl famously wrote: “Man’s search for meaning is the primary motivation in his life”. In other words, having a “why” to live for can help us bear almost any “how.”

From an evolutionary perspective, because humans can imagine the future, we benefit from long-term goals and overarching values to guide us. Meaning gives us a reason to plan and hope. On a personal level, pursuing meaning brings a sense of fulfilment that purely chasing pleasure or material success cannot provide. We care about meaning because it makes life feel worthwhile – it tells us our existence matters in a larger context.

Researchers in existential and positive psychology generally point to three reliable pathways for building a sense of meaning in everyday life:

Beyond these big three, modern clinicians highlight mindfulness and deliberate reflection as practical tools. Slowing down lets us notice the “micro-moments” of meaning – a kind word from a stranger, finishing a project, helping a neighbour. Regularly checking our activities against core values ensures that what we do still resonates with who we want to be.

Just as certain habits and attitudes help us find meaning, other factors can stall or derail our search for purpose. One common trap is falling into what Frankl called the “existential vacuum” – a sense of emptiness and meaninglessness that can creep in when we lose sight of our why. This often manifests as boredom, apathy, or the feeling that life lacks direction.

When we experience a lack of meaning, we may try to fill the void with short-term pleasures or compulsive behaviours. These coping mechanisms might give us a temporary break, but they end up hindering our ability to take action and find meaning in life. In other words, chasing fleeting pleasures or suppressing our emotions might distract us from the deeper struggles we face, but it prevents us from growing and evolving as individuals. The discomfort essentially pushes us to confront the need for meaning.

Several mindset traps often derail the search for purpose: waiting passively for life to hand us meaning, chasing short-term pleasure or status instead of deeper fulfilment, and letting fear keep us in unfulfilling routines. Spotting these patterns and pausing to ask which deeper value we’re neglecting when we distract ourselves opens the door to reconnecting with what truly matters.

Ultimately, the search for life’s meaning is a deeply personal journey that touches on many aspects of our being – our relationships, work, beliefs, and dreams. A holistic approach to meaning might involve nurturing all these areas: building loving relationships, doing work or hobbies that excite you, caring for your community, and taking time for reflection or spiritual practice. It’s about aligning your life with your values and being who you truly are meant to be.

It’s also important to remember that meaning is not a one-time discovery, but an ongoing process. Our sense of purpose can evolve over time or through different life stages. At Anima, we recognize the importance of this quest. Our AI-driven platform uses attention bias metrics to help illuminate what draws your focus and emotions, offering insights into what you find meaningful (or where you may feel a void). We even offer a specific AI-guided topic dedicated to finding meaning and purpose. This personalized tool can accompany you in exploring your values, identifying passions, and overcoming mental blocks on your path to a more meaningful life. In the journey of searching for life’s meaning, you’re not alone – and with the right support, you can discover purpose even in places you hadn’t thought to look.

References